The Codex - Entry 0000: Press Start

A brief introduction to an unnecessarily long and complicated project

Let’s start with the truth: This was never meant to be a Substack. In all my wildest dreams and imaginings, my goal was for The Codex to be a series of books. I’d still like that someday! But first—

I have a lot to say in this post, but the quick pitch is this: The Codex is intended to be an obsessively comprehensive historical survey of role-playing video games. I plan to start at the beginning—and I mean the very beginning—and to have entries on every game possible, including some that are no longer even playable. I’ll get into more specifics below, but my goal is for each of these entries to be deeply researched and provide everything you would need to know to understand what the game is, how it plays, its historical context, and so on.

Since I’m now launching this project on Substack rather than as a book, I’m also going to use that opportunity to write about current RPG releases as well. So alongside my historical entries, I’ll provide my thoughts on some of the most interesting new releases. For example, I just started up Dragon’s Dogma 2 earlier tonight, and I’m looking forward to writing about it next week.

So why the shift from book to Substack? The main reason is simply logistical. This is an idea that I believe in and have wanted to do for, uh, most of my life at this point. But it’s not exactly a slam-dunk pitch to book publishers. Barring the likelihood of any sort of advance, The Codex became a project that was far too easy for me to keep pushing off, putting it on the back burner. Sure, it’s the thing I most wanted to spend my time on, but I had to focus on the work that would actually bring in money first. I don’t like it, but that’s the system we live in.

As one of the growing horde of recent layoffs in the tech, video game, and media spaces, I suddenly find myself with a lot more free time, and I’ve decided to finally take the leap with The Codex. Creating it as an online project rather than a book provides the gentle nudge I need to actually force myself to devote time to it, as well as perhaps a little bit of cash to keep me going. I’m not particularly expecting The Codex (or Cartoon Ghost as a wider Substack publication) to bring in enough money for me to live off of—though I’d be delighted to be proven wrong!—but I’m hoping it will be enough to at least give me some breathing room, to allow me to take a little less freelance or contract work and spend a little more time researching and writing about the stuff I’m most passionate about. And that stuff is RPGs.

Welcome to The Codex

For all the imagination and variety available in video games, role-playing games (aka RPGs) inhabit a unique space in the medium’s long list of genres. RPGs serve simultaneously as a solid form for video games and an empty shell that the components of a game can be poured into. RPGs can pull from a huge range of fictional categories, from high fantasy to horror to romance. They can also build on other gaming genres; it’s not unusual to run into, say, a first-person shooter, a platform, or even a sports game with an RPG backbone.

The argument could be made—and certainly the very existence of a project such as this supports it—that no other genre of video game has had as massive a reach as role-playing games. No other single style of game has so thoroughly enmeshed itself in the fabric of the medium as a whole.

If you accept that thesis—and if you care enough about RPGs to be reading this, I suspect you’re at least open to it—then it begs some questions. What is it about RPGs? Why has this genre lasted so long, spread so far, and proven so flexible, open to altering its own form to fit the needs of any individual game?

There are no easy answers to these questions. To some degree, searching for those answers is a lifelong process, the very reason for this project’s existence. Nevertheless, I’m going to offer a theory here, based on the ideas I’ve mulled over for the first thirty-odd years of my RPG-obsessing life. In all likelihood, this theory will change over the next thirty-plus years (allowing that I live that long), as this project continues and as the RPG genre ever evolves. But this is my starting point.

The Journey Begins

It’s nearly impossible to pinpoint the exact origins of the RPG as a concept. Role-playing games existed long before the creation of video game consoles or computer hardware that was used to develop and play games. Centuries ago, for example, battle and historical reenactments, while not technically games in the traditional sense, introduced many people to the idea of stepping into different identities.

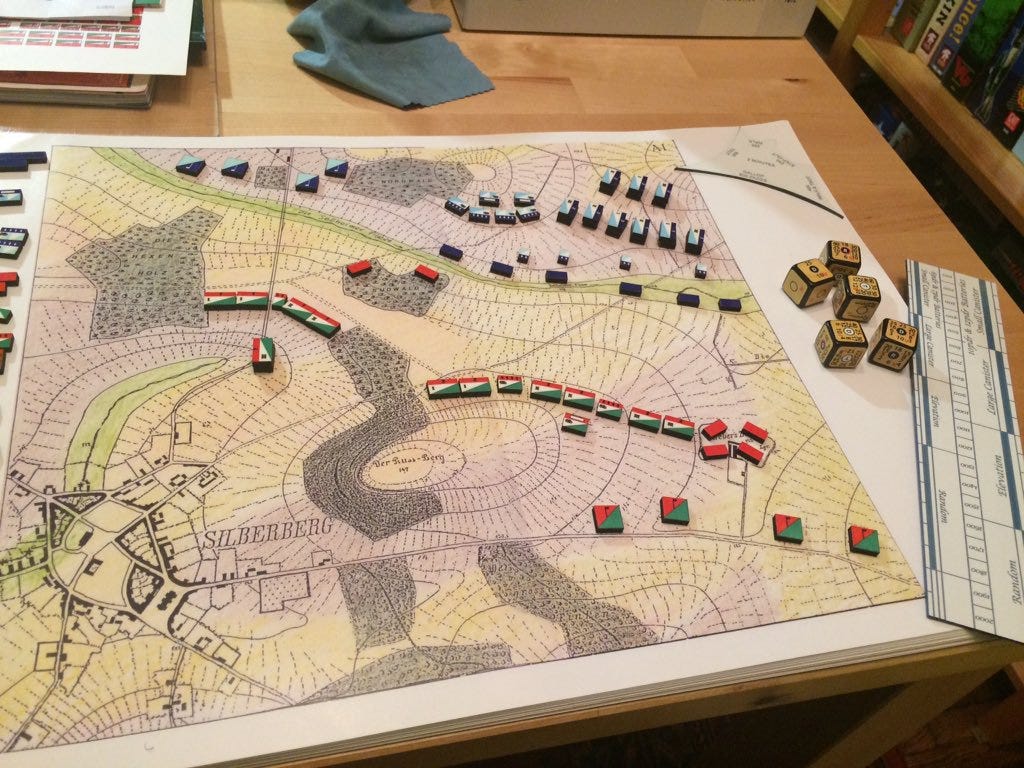

The proper roots of the RPG stretch all the way back to at least the 18th century, to some of the earliest examples of pen-and-paper and board games. Building off of ancient board games, a Prussian scientist named Johann Christian Ludwig Hellwig invented the first known wargame. Hellwig’s “wargame” (aka Das Kriegsspiel) expanded on the strategic elements of chess by dumping its simplicity. In what some may argue is the first ever example of inelegant bloat in game design, Hellwig juiced the complexity of his board game by increasing the size of the board, the types of pieces available, and the realism of the scenarios players would find themselves navigating.

Though far from what most people would consider a role-playing game in any modern sense, Hellwig’s wargame was literally meant to put players into a role—that of the commander of a large army. In fact, many contemporaries believed that Hellwig’s wargame, with its intricate mechanics laid out in a rule book of over one hundred pages, could serve as a legitimate learning tool for nobles with military service in their future.

Wargaming’s popularity grew around the world through the 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1913, beloved sci-fi author H.G. Wells got in on this booming source of recreation, publishing a book titled Little Wars, which operated as a rule set for children playing wargames with their toy soldiers. This was arguably the first expansion of classic wargaming into the realm that is now known as “miniature wargaming”—that is, wargaming centered around the use of miniatures, tiny toys that are often hand-painted by the players.

(Sidenote: The original full title for Wells’s book was Little Wars: A Game for Boys From Twelve Years of Age to One Hundred and Fifty and for That More Intelligent Sort of Girl Who Likes Boys’ Games and Books. Though condescending and laughable in a modern context, this was an early nod to the growing recognition that both games generally and role-playing specifically hold interest for all people, regardless of gender, age, race, and culture.)

By the mid-20th century, the nerdy niche interest of wargaming collided with the nerdy niche interests of fantasy and science fiction. Wargame creators and players alike started implementing more and more elements from the fantasy novels they loved, such as J.R.R. Tolkien’s absurdly popular The Lord of the Rings series.

Many different board games, wargames, and even prototype versions of live-action role-playing (LARP) were developed at this time. None have more historical importance, however, than Chainmail, a miniature wargame based around medieval combat that was developed by Gary Gygax and Jeff Perren and published in 1971. Future iterations of Chainmail added increasingly more fantasy elements to the game, as well as mechanics that would become RPG standbys, such as hit points—a numerical measurement of a character’s health—and experience points—a numerical measurement of a character’s growth and progress toward becoming stronger.

In 1974, three years after Chainmail’s launch, Gygax and Dave Arneson published Dungeons & Dragons. If everything else I’ve mentioned thus far is a primitive ancestor of role-playing video games, Dungeons & Dragons is a more directly related antecedent—a parent or grandparent, or perhaps a beloved aunt and uncle that have constantly pushed the next generation in specific directions.

In Dungeons & Dragons (often shorted to simply D&D), we witnessed all the staples of the role-playing video game: storytelling, character progression, strategic combat scenarios, dungeon crawling, and pages full of nitty-gritty stats and math to balance in your head. Not every RPG has every one of these elements, but virtually every RPG has at least one or more of them at its core. And as we will see throughout the first entries in The Codex, Dungeons & Dragons was a direct source of inspiration for the majority of the earliest role-playing video games, many of which were programmed by college students who were obsessed with the new pen-and-paper sensation.

The early history of RPGs that I’ve presented here is a brisk beginner’s course at best. There are dozens of games and hundreds of creators who were pioneers in developing new and engaging ways for everyone to while away the hours and explore new worlds. Thousands of pages have already been written on this subject, and there are many fascinating chronicles that I recommend checking out. Please take a look at the official The Codex Recommended Reading List for a continuously updated list of some of the best and most interesting sources I’ve consulted.

But on the same note, and as you will soon find out, many of these earliest examples of the RPG video game genre are either already impossible to play or at risk of disappearing soon. Many of the developers who created these first experiments with role-playing video games are reaching old age and, in some sad cases, death. Dungeons & Dragons cocreator Gary Gygax, for example, passed away in 2008.

As a culture, we have already crossed the point at which documenting this history is significantly harder than at any time previous to now. Whether that is meaningful to you or not depends on how much you care about role-playing video games; once again, if you’re reading this Substack and have read this deep into this post, I will choose to believe that, like me, you do care. RPGs changed my life, and I’m sure I’m not the only one. I want to understand where all these incredible, compelling, powerful adventures came from, how they evolved, and even those cases where they went horribly wrong.

Once More: What Is The Codex?

This project is not about the history of RPGs broadly, but rather the history of role-playing video games specifically. While the former has been covered extensively by fans, historians, and enthusiasts, depressingly little work has been done to lay out, honor, and archive the history of role-playing video games. The Codex Recommended Reading List includes some excellent work, but it’s still a fraction of what I feel this subject deserves.

For my part, I became obsessed with RPGs from a young age. When I was around ten years old, a friend lent me a dirty Super Nintendo cartridge. The title was splashed across the dingy case’s label in ornate letters: Final Fantasy III. It was a game unlike anything I had ever played. Where most games I had played up to this point primarily drew me in via controller-clenching mechanical challenge, Final Fantasy III hooked me on a more cerebral level. Its combat required critical thought rather than tight reflexes, and its emotional story tugged on my heart in a way that I hadn’t realized was possible in video games.

Here was a whole cast of tragic characters who grew and changed and beckoned me to fall in love with them. Here was an adventure that took me months to complete, and that was without even digging into its many secrets and subplots. And by the time I reached the end, I felt as though I had made new friends. I felt as though I, too, had grown and changed.

Final Fantasy III marked the moment that I understood that I would be playing video games for the rest of my life. From that powerful opening scene forward, RPGs became a particular obsession. I was always looking for more games in that style, chasing the high of discovering a new world that could suck me in and make me feel entirely transported.

In dozens of hours of research on my small-town library’s single internet-connected computer, I slowly began to piece together the puzzle of this strange new world of RPGs. I came to understand that Final Fantasy III was, inexplicably, actually Final Fantasy VI, and that there were five previous entries in the series waiting for me to play them, although not all of them had been translated into English at that point. I gained knowledge of other Super Nintendo RPGs like Chrono Trigger and Illusion of Gaia, as well as Western, mostly computer-based RPGs like the Might & Magic and Ultima games. I came to understand the subtle but meaningful distinctions that separated Western RPGs and Japanese RPGs, and the things that I loved about both. I made lists of games I would spend the next years asking for at Christmas and searching for on the shelves of used game shops. And I played everything I could get my hands on.

As I moved into my teenage years, then adulthood, and now staring down middle age, my passion for role-playing video games has never faded. Having played many of the classics and continued major releases in the genre, I’ve turned toward unearthing its history. I’ve spent years learning about Dungeons & Dragons, about the earliest RPGs developed for mainframe computers, and so on. But even as I’ve become more knowledgeable personally, I’ve hit walls in what is available; frustrations at having to dig through multiple sources to find even basic info; and recognition that older and more obscure games are at risk of completely disappearing from public awareness.

The Codex is my attempt to tackle these problems. It is intended to be an ongoing, essentially never-ending project dedicated to exploring the history of role-playing video games on a game-by-game basis. Some games are inescapably more important or more interesting than others. Inevitably I will have more to say about, for example, Baldur’s Gate than the third game in a line of handheld RPGs based on a long-running anime series.

But sometimes those forgotten games feature surprisingly meaningful content. They shouldn’t be ignored. My goal and my intention is not to neglect any games, to devote as much rigor as I can into researching the history of each title, as well as each game’s mechanical, ludic, and dramatic contributions to the genre.

In keeping with that goal, I will be taking the broadest possible approach to the definition of “RPG” in The Codex.

OK, Smart Guy, So What Is an RPG Then?

As with any genre in any medium, RPGs are simultaneously a lot of different things to a lot of different people.

Some fans have a very hard-line view of what counts as a role-playing game based on actual gameplay systems. For these players, a game may require one or two specific mechanics to be considered an RPG—such as gaining experience points or leveling your character up.

For others, player-centered storytelling is the key component to an RPG; if the storyline progresses down a narrow path with little or no input from the player, as in most traditional Japanese RPGs, it just doesn’t capture the role-playing experience.

Still others embrace a looser interpretation of the genre. Fantasy-themed games with limited stats and character progression but some dungeon crawling—such as the Legend of Zelda series—or story-heavy games with extremely minimal gameplay mechanics—such as some visual novels—might still fit into their characterization of RPGs.

What counts as a role-playing game for the purposes of this project? Well...all of it! In keeping with the amateur historical and archivist goals of The Codex, I will be taking the broadest possible approach to cataloging RPG video games. Inevitably, I will include some games that certain subsets of RPG players don’t agree with or don’t personally consider as RPGs. That’s okay. On my end, the goal is to be as inclusive and all-encompassing as possible. In some cases, I’ll even be covering games that don’t necessarily fit my definition of the genre.

While I’ll be maintaining a very open approach to what games are included in The Codex, I’ll still be approaching each of them from within a similar structure that emphasizes three key elements of the RPG genre:

Story - For some role-playing games, the story is little more than a bare-bones excuse for the player to delve into a dungeon. For others, it’s a hundreds-of-thousands-of-words epic full of plot twists and character development. Wherever a game falls on that scale, each entry in The Codex will lay out the plot of the game with full spoilers. If you’d like to learn about a game you haven’t yet played without compromising your own experience, you can skip this section entirely. In the other two sections, I will avoid spoilers as much as possible and give ample warning when I feel like a story spoiler must be given in order to fully explore a topic.

Gameplay - Whether it’s through combat, relationships with other characters, equipment management, or other systems, RPGs generally have some degree of mechanical complexity underlying everything else that’s going on. In each entry, I will look at the various systems of play in each game with an eye toward digging deep into how each title works rather than just providing a cursory glance.

Artistry/Craftsmanship - This is a little more vague than the other two elements, but what I meant to point to here is the level of detail and care that goes into developing even the least successful RPG. By the nature of how the genre operates, there is a certain thoughtfulness that one must employ to put together a game of this type, even an unsuccessful one. In this section of entries, I will dig into historical details about the development of each game, who worked on it, and the context in which it was created.

My open-ended approach to what fits the definition of an RPG is inspired by the work of Jimmy Maher, author of the fantastic gaming blog The Digital Antiquarian. When Maher sought to determine which games fit into the category of “ludic narrative,” he was himself inspired by the cognitive scientist George Lakoff, who once wrote that although robins and emus are both birds, the former is broadly seen as more representative of birds. Maher came up with four elements that show how representative a game feels of the ludic narrative style, but he was careful not to be held back by these elements.

“There may be edge cases which fail one of the tests, but which still have the ‘feel’ of ludic narrative,” Maher wrote. “As long as we’re reasonable about these things, it seems pointless to exclude them from discussion because of some arbitrary checklist.”

This, too, is my feeling regarding figuring out what counts as an RPG in The Codex. As this project progresses, there will be some games that heavily favor story over mechanics, and others that have virtually no plot but hours of combat or puzzles. The tension between story and gameplay—between narrative and mechanics—has been part of role-playing from its very inception. For my purposes, there is no strong argument to exclude any of these games from this documentation; rather, I’ll work to provide enough context and information on each title that you can decide for yourself if it is “RPG-y” enough in the direction that you prefer for your own interests.

Though my aim is to be thorough, there’s nothing precise or scientific about the process that I have in mind here. In all likelihood, the approach I take will evolve over time. Whatever forms it may morph into, I consider this a lifelong project. I’ve already spent years preparing for and putting together the entries I’ll be sharing soon, and in that time, my approach has already changed significantly from what I initially had in mind. I would not pretend to guess what this might look like in ten or twenty or thiry years.

I’d also like to give some special credit to those who inspired this project. As previously mentioned, there has not been a great amount of work done in the space of chronicling RPG video game history—but there has been some. In addition to the many sources that I’ll cite in each post and those tracked in The Codex Recommended Reading List, I owe a debt to several people.

The CRPG Addict (aka Chester Bolingbroke) has run an extremely thoughtful and entertaining blog for over a decade now where he plays through every computer role-playing game ever made. Though his approach is different from my own, his blog is utterly engaging reading and includes more in-depth research than almost anything else that’s out there. Discovering these posts was very much the genesis of my own interest in doing a similar project, and I cannot give a stronger recommendation: Please read The CRPG Addict if my work here has caught your interest at all.

Likewise, Dungeons and Desktops by Matt Barton has been and will almost certainly continue to be a crucial volume in my preparation for writing The Codex. It’s similarly focused only on computer role-playing games and provides a much less granular overview of the genre, but it is written with a careful, academic eye. It also helped me realize that there may actually be an audience for a project like this.

If you’re part of that audience, thank you for joining me on this journey. I hope that I can help you relive and discover a greater appreciation for the RPG video games that you already love, and I hope that I can also introduce you to new games you’ve never heard of or never realized you might want to play.

paid for a sub so i could ask “is pokemon an rpg?” but also bc i wanna support. you know i dont play many video games, but i love to learn and your writing is so good ❤️

RPGs have been a huge part of my life since about the same time as you (Final Fantasy 3/VI), but I feel like I missed a whole decade and a half of RPGs since I mostly played JRPGs. Even up to present day I've hardly played a CRPG or earlier western ones.

Will you be playing through the games you're talking about? I don't assume it's going to be a Let's Play type of situation, but I also don't know if you're going to go a more research paper approach vs a personal journey through the history of the games.